January 2008

Purpose

of the Trip

- Housing

- Potable Water

- Sanitation

- Energy

- Communications

- Agriculture

- Micro-Enterprises

Fr. Jack O'Hara and I arrived in Santo Domingo late at night. The following morning, we took a four hour ride west and north to Banica, which is right on the Haitian border.

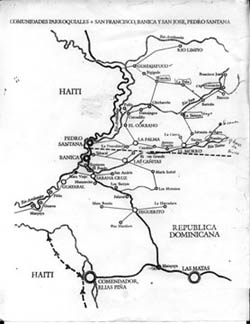

The Arlington (Virginia) catholic diocese operates two parishes on the border, one in Banica and the other in Pedro Santana, which is just a couple of miles north of Banica. Both of the parishes serve people in 30 to 40 villages ("campos") which are scattered great distances from the main church. Many of the campos of Pedro Santana are located high in the mountains ("las lomas"). I was able to visit about a dozen campos during my stay.

This is a typical street in Banica -- wide, paved, lined with houses, little traffic, especially early in the morning when this photo was taken.

The church plays a central role throughout the Dominican Republic. This church in Banica, the parish of San Francisco de Asis, has been served by a priest from the Arlington diocese since the early 1990s. Prior to that, it was without a resident priest for more than 20 years.

The Banica church is well built. Bells call the people to church one hour before Mass. They were glad to greet Fr. Jack, who had served in Banica for four years.

Each village ("campo") has its own chapel, due largely to the work of volunteers from Christendom College, George Mason University, and other colleges in Northern Virginia. This chapel in Sabana Cruz, about 2 or 3 miles from Banica, was one of the first built.

Getting to church in a truck is a luxury. This truck goes up and down the main road that passes the chapel in Sabana Cruz. People hop on the back. In most areas, the people walk for miles to get to their chapel, where Mass might only be offered once a month.

The people love the padre, and flock to see him after Mass.

This chapel at La Herradura is typical of chapels that were built some years ago, although it is somewhat unusual because the lower half of the walls are made of concrete.

This

chapel at Guaroa was built on a solid concrete foundation, a

characteristic of more recent chapels.

This chapel at Pilon is the newest in the Banica parish, having been completed in 2007. There are still no furnishings or seating inside.

I was able to visit one chapel in the Pedro Santana parish, in Guayayuco, one of the northernmost campos of the parish. To get there, we crossed the Artibonito river and took the International Highway (a dirt road) north for about 2 hours. On the left side of the highway is Haiti; on the right side is the Dominican Republic.

The highway cuts through the mountains ("Las Lomas"), roughly following the Artibonito river (below).

The International Highway crosses the river several times. You have to drive through the water; there are no bridges at most points.

The chapel at Guayayuco was the biggest I visited. It was built by the people a couple of years ago to celebrate some political event in the campo. Note the tire rim hanging in the doorway. That is the bell that is sounded to call the people to Mass.

The chapel was packed for the celebration of the feast of Our Lady of Altagracia. This is a big national feast day, the biggest feast of the year. Everything in the country was shut down so the people could celebrate the feast.

There is a wide variety of housing outside of the major towns. Some of the houses are made of twigs and mud, with thatched roofs.

Others are more sturdy, being built of wood, with metal roofs, gutters, and paint.

Some houses have solar panels (note the top of the roof) and a battery (enough to power one or two light bulbs for a few hours at night) provided through a government program. These systems do not provide enough electricity to support a refrigerator.

It is not uncommon to see living fences made from cacti around these houses. They keep animals away from the houses.

Most houses have no running water. Here in La Herradura people fill large buckets from the community well for their daily water supply. Even then, the water is not potable without some form of purification. The diocese of San Juan de la Maguana has a filtration system that they can sell to people for about $12 U.S. It is a hard sell to convince some people that they need the filter system.

We visited a friend of Father Jack's named Mariana. She and her family (husband and four children) used to live in this shack until Fr. Jack asked a friend of his in Virginia to help them build a new house.

This is Mariana's new house. It is also a corner store ("colmado") that helps support the family.

The front of the house is the store. The family lives in the back of the house. Mariana hopes to expand the store soon so that she can better serve some workers who are expected at a biofuel factory that is slated to be opened later in 2008.

Three of Mariana's four children were home when we visited. They were thrilled to get stuffed animals that Fr. Jack had brought from the U.S.

Fr. Pedro Mateo, ordained in 2007, was the first priest ordained from the Banica parish. We visited his parents at their farm where they live with two of their sons. The fields that they farm are quite a distance from the farm.

Fr. Pedro's mother emerges from the house (note the solar panel on the roof and the gutters for catching rain water). The farm is located in Pilon, a few miles from Banica but part of the Banica parish.

Shown: Fr. Jack with Mrs. and Mr. Mateo, Homero (from the parish), and a neighbor.

Each community has an elementary school. All the ones I saw were one room schools such as this one in Guaroa.

I did not have a chance to observe the type of education students get in these schools.

A few of the campos can still be reached only by foot (this is not one of them), along narrow paths.

Although we

traveled by car (the Land Rover is most popular), many of the locals

travel by burro. (Note that this young boy has several jugs on

the left side of the burro. He will fill them and bring them

home. They will be his family's water for the day.)

Others travel by mule. This is how they get from place to place and how they cart their goods from home to market.

This is one

of the better roads that connect the villages ("campos") once you leave

town.

On the

Haitian side of the Artibonito River, women start fires to prepare

breakfast at a Haitian market.

The

Artibonito River separates Haiti from the Dominican Republic. People

wade across it and bathe in it each morning.

These people

have come across the river ready to sell their goods at the Sunday

Market in Banica.

The Sunday

Market in Banica is a colorful event that draws people from throughout

the region, both from Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

It is not unusual to see animals "parked" by the roadside or in a field while their owners are at the market.

Mules

wait on the Dominican Republic side of the Artibonito, having brought

their owners to market from the Haitian side.

There are

signs of improved housing in some places, such as this house in

Guayayuco, two doors from the church.

Construction

is halted for now, but this will be the best home in Banica. All

concrete. Larger than others.

Potential is

coming to Banica in this BioFuel factory that will turn castor oil

beans into commercial oil and bio-fuels.

From Banica, we set out to visit Fr. Jack's friend, Junior Charles, in Hinche, Haiti. We crossed the Artibonito River in Pedro Santana, then picked up this national highway in Haiti that runs from the border with the Dominican Republic to Hinche. The highway is shared by pedestrians, animals, cars, and trucks.

These are plains along the road between the border and Hinche, a beautiful part of the ride.

It was not a smoothe ride. Ruts like this were not uncommon. As a matter fact, they are found throughout the route. It took almost 4 hours to make the 35 mile trip.

After many ruts, river beds, and very deep mud, it happened. The first of three flat tires we would have on this round trip. Fortunately, the spare tire was good. We did not tie up traffic for too long. There was no room to pass us, but no cars came along while we changed the tire.

We had to cross the river several times. Thank goodness it was the dry season; can't imagine the rainy season.

We came

across a truck that had overturned and blocked the highway. Everything

had to be offloaded to upright the truck.

It looked like their cargo was mostly charcoal, plus the 20 or so people who were riding in and on the truck.

We also came across a spot where the highway was blocked by a construction project, building a new wall for a house.

Our destination was Hinche, a city of about 100,000 people. This cathedral has been in use for over 500 years.

This new cathedral is now used for most church services. Could not get interior photos because it was locked.

There are

few cars in Hinche, and oxen still play a large role in moving goods

around the city.

Pedestrians, autos, motorbikes, oxen, and mules share the streets of Hinche.

The cathedral rectory, where we stayed, is one of the better residences in Hinche.

Mule power,

horsepower, and human power are abundant throughout Hinche.

We saw a few light posts in the city but the streets were dark at night. No homes or businesses have electricity.

Students walk to and from school, usually in small groups.

We were glad that Hinche had this tire repair shop to fix our flat tire. They fixed it over night. (Note: The owners of the tire shop probably live in the shipping container on the left.)

We had come to visit Fr. Jack's friend, Junior Charles. He lives at the end of this street, typical of many in Hinche.

Fr. Jack had this house built for Junior and his mother after an accident left Junior paralyzed.

Junior was quite ill so we brought him to a clinic in Thomasique. A group of visiting American doctors treated Junior immediately. He got excellent care that day and for several weeks of recuperation.

St.

Joseph's Clinic was built and is supported by Medical Missionaries, a

group of volunteer doctors and nurses from Northern Virginia. It

serves about 100 to 150 patients each day and facilitates more than 40

births each month.

This residence, on the same grounds as the clinic, houses volunteer doctors and nurses who come from the U.S. every couple of months, as well as two pre-med students who volunteer to work at the clinic for an entire year. The clinic is staffed full time by four Haitian doctors, a nurse, a mid-wife, and various other staff..

When not

caring for the ill, the volunteer doctors can enjoy this view of Haiti

from the back deck of the residence.

This sunrise in the Lomas between the Dominican Republic and Haiti provided a nice transition for our return to Banica and Pedro Santana.

On our way

back to Santo Domingo, we stopped in the mountains to visit Fr. Pedro's

parish. It is located in the mountains, in Peralta, outside of

Azua.

This is housing we passed on the way through the mountains from the highway to Fr. Pedro's parish.

Nuestra senora de Lourdes is one of two parishes where Fr. Pedro serves, in addition to working at the minor seminary in Azua.

The church is spacious and simply but reverently outfitted.

We had just enough time before our return flight to stop in Santo Domingo and visit the Cathedral, which I believe is the oldest Cathedral in the New World.

That's the end of my story of this trip. If you'd like any additional information, or if you have any questions, you can contact me at:

Peter

J. Dirr, Ph.D.

peterdirr@gmail.com

peterdirr@gmail.com